FILM FILINGS 10/19/2023

JORDAN M. POSS: THE LAST KING

CHRISTOPHER WITTY: THE WOLF MAN

SAM STEPHENS: THE DEAD

NATHAN GILMORE: SILENCE

Hello, readers! This is the maiden post of Nathan Gilmore as Film Filing’s new editor. Sam and I share a wide swath of our tastes in movies, with some significant deviations,

I moved away from “liking movies” to “appreciating them” in Mr. Smith’s Film Appreciation class in high school: one watch of “Citizen Kane” was all it took. Tastes these days run to a lot of historical dramas, indie movies and foreign films.

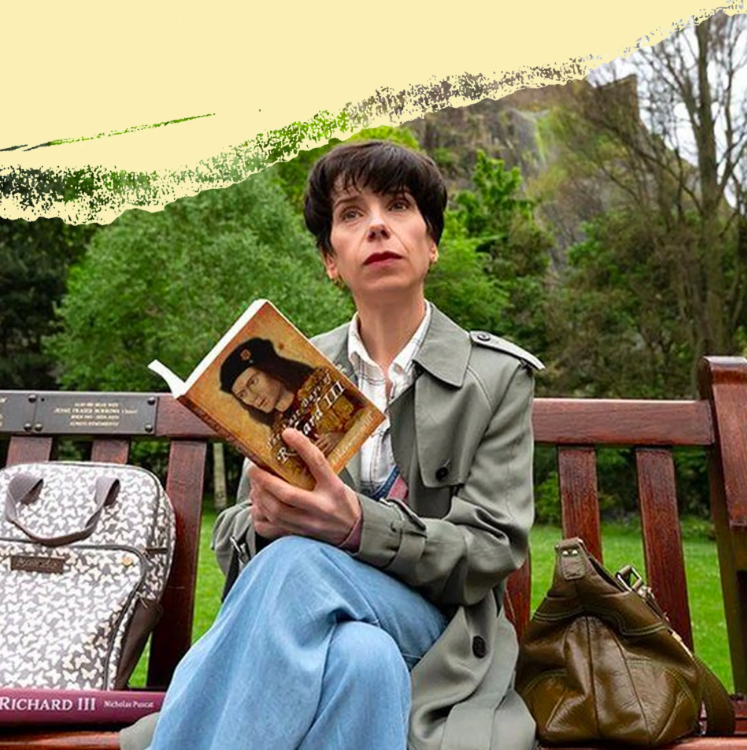

JORDAN M. POSS: THE LOST KING

Over on his blog, Jordan M. Poss reviews a movie about that most notorious of kings, Richard the Third. The Lost King (2023) is the story of one woman’s quest to rescue Richard from the scrap-heap of history. Poss writes:

But while the object of Langley’s quest is Richard’s bones, the movie is really about Langley. Suffering from ill-health and the misunderstanding or outright hostility of others, she sees herself in Richard, and to find and restore him to a royal tomb is also to find and redeem herself. Once she has done this, her apparition of Richard—clothed, at last, in the royal arms—can depart, and she can accept a humble life of telling others her story.

Despite what could have been a silly conceit—a ghost king following the protagonist around—this is all wonderfully written and movingly executed. As a movie, The Lost King offers wonderful light drama. But I couldn’t avoid asking some questions about its own treatment of the past.

CHRISTOPHER WITTY: THE WOLF MAN

Over on his FilmFolkUk Instagram page, in the spirit of the season, Christopher Witty gives us a review of Curt Siodmak’s seminal classic “The Wolf Man”. Witty finds a lot to like in this pop-culture stalwart, and you will too. Here’s his review in full:

The Wolf Man (dir. George Waggner, 1941). Written by Curt Siodmak (author of Donovan's Brain and co-writer on Jacques Tourneur's excellent I Walked with a Zombie (1943)), The Wolf Man is one of the defining monster movies produced during Universal's golden age, completing a symphony of horrors that included Dracula (1931), Frankenstein and The Bride of Frankenstein (1931/1935), The Mummy (1932), and The Invisible Man (1933), eventually resulting in daft monster mash-ups like House of Frankenstein (1944) and the Abbot and Costello Meet ... run of films that dragged the franchise out into the 1950s.

I like The Wolf Man almost as much as the Frankenstein films. In Danny Peary's book Cult Movies, he argues a strong case for Lawrence Talbot (Lon Chaney Jr.) being a classic figure from film noir. If you consider that he kills only when he's transformed into a werewolf, in a round about way he's the wrongfully accused man who begins to realise he might be a killer after the evidence mounts up against him.

Inhabiting a kind of netherworld where the old meets modernity, Talbot is an outsider. After a prolonged absence, he arrives at his ancestral home in Wales in a car, yet the town, with its horse-drawn carriages and Romanian gypsies resembles a European village from the 19th century. This amorphous setting, however, is due to Universal doubling their backlot sets for different films set in various locations and time periods. Talbot, too, feels misplaced as an American whose father (Claude Rains) is an English lord. This was also due to behind the scenes tinkering: in Siodmak's original screenplay, the British Talbot was visiting Scotland to install a telescope (a remnant of the script that made its way into the film when Talbot first lays eyes on Gwen (Evelyn Ankers) through her bedroom window), but the casting of Chaney caused for an American character to enter the fray. Chaney's presence can be quite jarring at times, especially during the scenes between he and Rains, who never convince us as father and son. But it also adds to his doomed outsider status, making the suspicions surrounding him more effective.

Deeply atmospheric, the fog shrouded countryside and night shots of the village look amazing, and the lap-dissolve transformation scenes still stand up quite well for a film that's edging its way to its centenary. You also get a small role for Bela Lugosi as a fortune teller and a great turn from Maria Ouspenskaya as his Romani partner, who gets the best lines as she warns Talbot of his inescapable fate. Five star entertainment.

SAM STEPHENS: THE DEAD

Sam Stephens gives a brief yet heartfelt review of John Huston’s adaptation of James Joyce’s “The Dead”. The cold chill of the Irish winter that suffuses the film makes it perfect for fall viewing. The review:

Based on the short story by James Joyce, this is a film about a party held in the late evening. It’s hosted by and held for three sisters whose work in the community is much celebrated. But that’s only part of the picture. Guests arrive. They sit and discuss a lot of things, and like the other attendees, I sit and listen as well. So involving is the banter, so human the littlest foibles between kin, that there is no use wishing it were a different kind of movie. You are stuck at a party you have an obligation to attend, but eventually you accede to its demands and enjoy yourself. Lesser filmmakers could pull this off for ten minutes at the most before it started to drag. But Huston started directing—already an accomplished screenwriter in 1941, and he’s had a few lessons: The Maltese Falcon, Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Key Largo, The Asphalt Jungle, Moulin Rouge, Beat the Devil, The African Queen, Moby Dick, The Man Who Would Be King, Annie. Even so, it’s quite a feat.

Then, there is the post-party and the sadness that was warded off returns home with you. Donal McCann’s internal monologue at the end is supremely haunting and beautifully set over winter images of Ireland at night. Anjelica Huston stars in her father’s last film. Highly recommend this wonderful movie.

I first saw part of this film in college for a film class. We watched only the last 30 minutes. This led me to believe that whole time that this was a short film. It is not—it’s a little over 1 hr 20min. I watched the full film maybe a month ago, and it lingers quite vividly as I write this review.

P.S. The DVD cover is very silly, presenting a smiling Anjelica with a rose, as if she’s some mischief-causing Jane Austen heroine.

NATHAN GILMORE: SILENCE

Over on his Instagram page Nathan Gilmore offers a response to Martin Scorsese’s historical epic “Silence”. A movie of probing insight and deep spiritual rigor, it asks us to examine the nature of faith in the face of abject horror.

Work out your faith with fear and trembling. Martin Scorsese reportedly read Shūsaku Endo’s 1966 novel shortly after his “The Last Temptation of Christ” came under fire from the Catholic Church and conservative Christian groups. One can imagine, perhaps, that Scorsese found some solace in identifying with persecution and fidelity to one’s beliefs in the face of intense pressure.

That’s, on one level at least, what “Silence” is about. The plot centers on two young priests and missionaries to Japan, Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) and Garrupe (Adam Driver) who hear that their mentor and confessor, Father Ferrera, has renounced his faith and is living on the island with a Japanese wife. They leave Portugal for Japan to investigate.

The two men make an interesting pair. Rodrigues looks younger, and his fresh-faced enthusiasm is a foil to Garrupe’s world-weary realism. (Just for their faces, Garfield and Driver fit their roles well). They are captured by the Japanese authorities, and their imprisonment forms the basis for the second half of the movie and the meat of the moral questions it poses.

The Japanese imperial government’s position on Christianity is straightforward: Christianity is a cancer that must be eradicated from the nation, and those who spread it must be stopped.

You might think the priests’ position is similarly simple. It isn’t. If Rodrigues is passionate and headstrong, and Garrupe is a little more grounded in reality, their erstwhile mentor has completely lost his faith. Here, too, Scorsese complicates things. We are given a triptych of belief, a scale of faith: a believer, a questioner, an apostate.

Ferreira’s apostasy is a strange thing. He was tortured into recanting his faith, but here as an older man, he’s not bitter or broken. His disbelief takes a far more rational cast than a scream of denial wrenched out on the torturer’s rack. Maybe, he reasons, Christianity doesn’t belong in Japan. He shares this view with the Japanese Inquisitor, who adds to Scorsese’s complications by being a rational, even practical and intelligent, man and not a monster.

This is where “Silence” speaks the loudest. It is an intensely spiritual film, and I found myself exercised during parts of it, not because I did or didn’t believe the same things the characters did, but because I wasn’t sure if I could believe how they believed. Faith comes easily sitting in a pew on Sunday morning. Tied head-down to a stake in a Japanese prison camp? That’s a different matter— a different kind of faith, no matter what anyone says. It’s easy to say that the cruelty of the Japanese discredits their faith, but it throws the question back on Christianity: Christian morals may be better, but do they offer any escape from the horror of torture that is more than a moral victory?

It’s likewise easy to say, from the Christian perspective, “Though he slay, yet I will trust”; but when the actual process of slaying is happening, it’s not easy to trust. What happens when your faith is the cause of others’ suffering? Would your faith demand you hold onto it, or act as it says it would have you— with mercy? Would it have you deny it superficially in order to follow it fully? The Inquisitor says it himself: you don’t have to deny it in your heart, you just have to say the words. But Christianity has never made much distinction between belief and speech: “If you confess with your mouth”.

Scorsese doesn’t answer these questions outright. The general bent of the movie is toward idealism, toward faith, toward self sacrifice— even when that leads to the weakest parts of the movie. The artistic sins here are all that of cheesiness, of overstatement. I think we understand the inner state of a priest through dialogue and context, and the face of Christ didn’t need to magick itself into the surface of a pond. There are a few Mel-Gibsonesque touches that I have never cared for: the superfluous use of slow motion, the random extreme closeups that are meant to convey seriousness or grandeur but come off as amateur, the ubiquitous chorus in the background singing incessant aahhhhhs.

But these are cosmetic quibbles. The movie has a good heart, and an earnestness that excuses a little of its self-importance. Those hard questions remain. I will say, without giving too much away, that he does find a kind of answer. It is not the one I anticipated, or felt comfortable with. Like the outset, the resolution of the film obstinately defies an easy, or even livable, answer.

But I don’t think Scorsese, or Endo, for that matter, are very interested in easy answers. Nor is truth always found in the easy answers. For if truth is objective, then it is we who must move around it, accommodate it. Faith, it seems, functions best as an ongoing experiential process that allows for modulation in the face of life’s vicissitudes. Find your own way. Work it out, not cavalierly or with nonchalance, but with fear and trembling.